Fairfax County General :

Fairfax Underground

Welcome to Fairfax Underground, a project site designed to improve communication among residents of Fairfax County, VA. Feel free to post anything Northern Virginia residents would find interesting.

Welcome to Fairfax Underground, a project site designed to improve communication among residents of Fairfax County, VA. Feel free to post anything Northern Virginia residents would find interesting.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

Dogue Creek Village Ft Belvoir

()

Date: July 21, 2014 08:55AM

Hi everyone, I used to live in Dogue Creek Village on Fort Belvoir years ago. Before the homes were remodeled my family had been in DC all the day with my godparents and their children. When I spoke with my friend (who lived next door) the next day she asked me who we had at our house. I told her no one had been home the day before because we were all out sightseeing. Then she told me that all day she and her parents heard people running up and down the stairs. They also heard people talking, and they even heard laughter. She said that it sounded like we were having a party, and when she came over and knocked on the door everything went silent. Then when she left the noise started up again. We lived in what might be considered a townhome apartment, so you could hear through the walls quite easily.

Anyone else had any ghostly going on's in Dogue Creek Village or on Fort Belvoir itself?

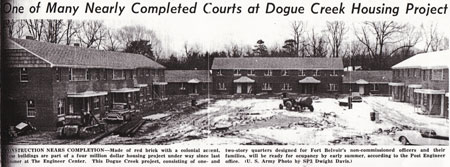

Dogue Creek Village, construction, Jan. 27, 1956

Attachments:

Anyone else had any ghostly going on's in Dogue Creek Village or on Fort Belvoir itself?

Dogue Creek Village, construction, Jan. 27, 1956

Attachments:

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

my old house is haunted

()

Date: July 21, 2014 09:16AM

My old house at 3912 Teakwood Ave, Richmond, VA is haunted. I lived in it fourteen years. The last three were the scariest of my life. I spent over five thousand dollars and hired some of the most famous people in the medium to clear it. We were never really successful. Currently Bobbie Atristrain has a book out and the last chapter is on the house, it is called Haunted People haunted Minds. I am also writing a book. There are witnesses, photos and when i sold it, i told everyone who wanted to look that it was haunted.

Attachments:

Attachments:

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

Sally Fairfax Ft Belvoir ghost

()

Date: July 21, 2014 03:36PM

The Lady of Belvoir

http://www.virginialiving.com/virginiana/history/the-lady-of-belvoir/

If there is a ghost at the Fort Belvoir military base in Northern Virginia, it is that of Sally Fairfax, wandering about her garden, admiring her favorite daffodils while eagerly listening for the sound of hoofbeats and the approach of her young caller: George Washington.

In the spring, the daffodils still bloom, but Belvoir is no more. Long ago, the charred ruins of the lovely mansion crumbled to the ground along with its memories of candlelit balls and the sounds of coaches on cobblestone. Yet a love story remains. It is little known and less spoken of, but still an integral part of America’s colonial history. It is a chapter in the life of the American hero, George Washington, who loved, passionately, the lady at Belvoir his neighbor and the wife of his best friend, George William Fairfax. Proper credit has never been given Sally for the important role she played in Washington’s early life. Instead, she has been regarded mainly as a flirtatious Southern belle, a brainless beauty. Untrue!

The eldest and most fascinating of the four daughters of Col. Wilson Cary, owner of Ceelys Plantation near Hampton, Sally was born in 1730 to great wealth and luxury. The Cary plantation was the center of society along the lower James River. Gentry from near and far often visited, as did officers from foreign ships that sailed into port.

As the colonel was a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, the family, during sessions, stayed at their Williamsburg townhouse and took advantage of the town’s many social events, including Assembly balls at the Governor’s Palace. A strict guardian of his four pretty daughters—Sally (Sarah), Mary, Anne and Elizabeth—the colonel was quick to discourage any suitor who was not wealthy, not from a prominent family or otherwise unacceptable as a future son-in-law. He was particularly selective of Sally’s beaux for, as everyone knew, she was his favorite. He had personally overseen her education. Let a man without wealth or family background approach the colonel for permission to call upon Sally, and he would be sent packing with the words, “If that is your mission here, sir, you may as well order your horse. My daughter is accustomed to her coach and six.”

Sally, at age 18, was highly educated and intelligent, knowledgeable of world affairs, music, art, literature and dance. She read books from her father’s vast library. She was also feminine, a coquette—and, as yet, unmarried. Many of her friends were not only married but had become parents as well. Not that Sally seemed to mind, for beaux were still plentiful and parties numerous, and she had every material wish fulfilled by her doting father. She spent her days visiting friends, attending teas (often with her mother or sisters) and learning the latest gossip of Williamsburg.

Her evenings were for merriment. It was no surprise when the family received an invitation to attend the Governor’s Ball during the session of 1747. What was serendipitous was that Sally would meet her future husband, George William Fairfax, that evening. As everyone knew, he was from Northern Virginia and lived at the magnificent Belvoir mansion on the Potomac, along with his father, Sir William Fairfax. And he was heir to the famous family title that would one day make him Lord Fairfax.

Sally was expert in dancing, and she dressed expensively, her auburn hair coiffed beautifully by her attendant. She at once caught the eye of the 23-year-old Fairfax. He also caught Sally’s attention, with his powdered wig, handsome evening costume and aristocratic features. Each queried friends about the other. When George William learned that not only were the Cary women beautiful but also from a family of great wealth, property and history (dating back to the 1400s in England, as did his own), he at once asked to call on Sally. He was accepted by the entire family, one of whom informed him, “I know of no family which has ever possessed nobler specimens of womanhood.”

George William was hooked. He at once wrote to his cousin, Robert, in England, the only man who stood between him and the Fairfax title: “Attending here on the General Assembly, I have had several opportunities of visiting Miss Cary, a daughter of Colonel Wilson Cary, and finding her amiable person to answer all the favourable reports made, I addressed myself and having obtained the young lady’s and her parents’ consent, we are to be married on the 17th instant. Colonel Cary wears the same coat of arms as the Lord Hunsdon.”

Col. Cary thoroughly researched the Englishman’s background and happily discovered that not only did he stand to inherit Belvoir, with its 2,700 acres in northern Virginia, but he also owned properties in Yorkshire; the famous Leeds Castle in England was among the Fairfax possessions. Yes, if asked, he would be pleased to hand over his daughter to such a prominent man, never mind that there was an arrogance about the future lord, a noblesse oblige that puzzled some and awed others. Love had little to do with it.

How did Sally react to all this? She was dazzled with the prospects. One day, she reasoned, she would become Lady Fairfax. None of her friends could make such a claim. Belvoir would be her home, to live in, to entertain in, to do with as she liked. She had heard much good about the Fairfax men and their great wealth and position in the colony. And so, on the 17th of December, 1747, she and George William were married and at once left for Belvoir, the mansion perched high on a bluff above the mighty Potomac.

As the coach rounded the curved drive in front of Belvoir, Sally caught her first glimpse of her new home and at once fell in love with it. Built by her father-in-law, Sir William Fairfax, who was still in residence, the mansion was without a hostess as the owner was a widower and lived there with his two sons, George William and young Bryan. His two daughters had married well: Anne to Lawrence Washington, the neighbor at Mt. Vernon, and Sarah to John Carlyle, the merchant prince at Alexandria, short miles from Belvoir.

Seeing Sally’s awe of the mansion, George William is known to have commented, “It’s a nice little cottage in this wooded land.” Indeed. A large hallway ran the width of the home, allowing river breezes to cool the interior. Off the hall were four high-ceilinged rooms, all magnificently furnished with carved mahogany and cherry furniture. Persian rugs covered the hardwood floors, and oil portraits and landscapes hung on the walls. Sally’s own chambers were equally extravagant: There was a great curtained bed with steps leading up to it, a dressing table with large mirror in gilt frame, a chest on chest of drawers, comfortable chairs, a tea table complete with silver tea service and candelabra, and a large fireplace.

While Sally was delighted with the estate, she completely lost her heart to Belvoir’s magnificent flower garden, 160 feet wide and 215 deep. Patterned after a garden in the county of Stirling, Scotland, the garden contained tulips, violets, roses, hollyhocks and her special flower, the daffodil, of various varieties.

Determined not to become overwhelmed by all this grandeur, Sally soon took her place as chatelaine of this new mansion. Neighbors told her that it outshone the other Potomac homes—Mt. Vernon of the Washington family and Gunston Hall, George Mason’s home. Her husband, eager to show off his prized new bride, suggested an evening when she would meet his family and friends from Alexandria and the neighboring area. And they soon came for an evening of festivity, not only including dinner but dancing as well, as was the custom of the times. No one knows exactly what Sally wore that evening to greet her guests, but perhaps it was the gown that would one day be returned with her personal things to the Cary family and now rests, carefully cared for, in the Valentine Richmond History Center in Richmond: an off-white silk brocade gown embroidered with multicolored flowers. Pearls were the fashion, and it is known that Sally had beautiful ones to wear.

And the guests? Among them were John and Sarah Carlyle, her new sister-in-law, with whom Sally would soon become good friends. The Lawrence Washingtons were there as well: Anne Washington, George William’s other sister and, loved to dance as much as Sally did.

With the Washingtons that night came a tall, broad-shouldered young stepbrother, George Washington, who now lived at Mt. Vernon. Lawrence had invited him. The young man stood before Sally, staring at her steadily, for never had he seen such an elegant woman. Manners would have kept Sally from staring back, but briefly she saw the tall 16-year-old, fresh from the farm where he had lived with his mother and other siblings. He was plainly dressed, his dark brown hair drawn back from his strong face in a queue, large hands and feet waiting for the rest of his frame to grow into them, George Washington continued to stare at Sally with a masculine assurance, head held high, looking directly into her eyes with his own of blue-gray.

The evening was lively, with good food, conversation and dance. When it ended, Sally invited George to visit as often as he chose. He chose to visit very often, and was awed by how knowledgeable was the wife of George William. They spoke of books and plays. Sally introduced him to Joseph Addison’s play Cato (1713) and gave him her own copy, which she had brought from Ceelys, to take home and study. George studied it carefully, and when they met again they acted out portions of the drama, with Sally being Marcia and he, Juba. Often and throughout his life, in person and in letter, George would refer to Sally as “Marcia.”

A great friendship sprang up between Sally and Washington. The Fairfax men, Sally soon realized, were eager for the young stepbrother of their neighbor to improve his mind and achieve a career for himself. Unlike his two brothers, George had not had a formal education; his father had died before he could send him to England for schooling. While Lawrence wished that George would follow his own career at sea, George’s mother put an end to that idea. And so now his education would be up to his brother and the Fairfaxes, including Sally.

Sally took her task to heart. She instilled in him a desire to make something of himself. She read to him about famous leaders throughout history, urged him to enter the military and to achieve, achieve, achieve. She helped him with his writing and spelling, and with his manners in social and political situations. In addition to all this, the Fairfax men introduced him to influential military and political leaders. When the Fairfax cousin, Lord Thomas Fairfax, owner of almost all of Northern Virginia and land farther to the west, came to stay at Belvoir for a year, he at once took a liking to young George and wrote to George’s mother, “Young George has what my friend, Mr. Addison, was pleased to call the intellectual conscience. The Lord deliver him from the nets of those spiders, called women, who will cast for his ruin. I wish I could say that he governs his temper for he is subject to attacks of anger on provocation, and sometimes without just cause. But, time will cure him.”

The letter summed up the elderly lord’s opinion of women, for he had never recovered from being jilted on the eve of his own wedding by an Englishwoman. His attitude toward them, however, did not sway young George, who, as everyone knew, had had many youthful crushes on girls. Despite the difference in attitudes, the two men became good friends, and when Lord Thomas asked George to survey his lands to the west, he accepted at once.

This surveying trip, made with Sally’s husband, George William, gave Washington a boost of confidence. He was now earning his own money and gaining a knowledge of terrain he had not visited before. He matured rapidly.

Meanwhile, Sally busied herself with hostess duties. When foreign vessels docked at Alexandria, the ships’ officers were invited to Belvoir for evenings of dinner, dancing and entertainment. Sally, in her finery, the latest fashions from Philadelphia and New York, was at her best. To offer a good table was a point of honor of every hostess, and Sally had been well schooled by her mother. Breads and cakes were baked daily, the woods around Belvoir were full of game and the river with fish, and from farther downstream came oysters and crabs. There were vegetables, grown in the Belvoir garden, as well as wines: Madeira, claret and port were served along with beer made from the native persimmon.

One evening as she danced with George Washington, Sally mentioned that she was surprised at his expertise with the dance. He replied that his mother was an expert dancer and had taught him herself. Sally saw that he knew all the country dances as well as the Virginia reel and needed only a little more teaching about the minuet, which she was happy to provide. If her husband, an undemonstrative man, noticed their closeness, he was tolerant and never voiced an objection.

Not so his younger brother, Bryan. He scolded Sally about her flirtation with George. This annoyed Sally, who told her husband of Bryan’s remarks, and the subsequent rift between the two brothers lasted for quite a time. Sally never really forgave Bryan for what she felt was his intrusion into her life.

By now, George had begun a military career and was being talked about. He was showing great promise as a leader. He would write Sally from various camps where he was on duty, and in one such letter he writes, “I should think our time more agreeably spent, believe me, in playing a part in Cato with myself doubly happy in being the Juba to a Marcia as you must make.” He then quotes from the play: “And in the shock of charging hosts remember what glorious deeds should grace the man who hopes for Marcia’s love.”

When George’s fascination for Sally turned to love, it is not known. But his letters grew warmer as he matured, and when Sally suspected that they were becoming amorous, she suggested that he continue to write but to direct them in care of a friend and she would get them.

When George visited home, he found that Sally was usually busy with her friends. In 1755, he writes her, apparently frustrated: “I have hitherto found it impracticable to engage one moment of your attention. If these are fearful apprehensions only, how easy to remove my suspicions, enliven my spirits and make me happier than the day is long by honoring me with a correspondence which you did partly promise to do.”

Sally, not wanting him to stop writing or visiting, continued to receive his letters and visits. Each time she inspired him to climb higher, telling him he was destined for greatness. And each time his passion for her grew—though he held these emotions under a rigid control, for now was not the time to express his feelings. Yet, years later, he would speak to Martha Washington’s granddaughter and say, “In the human being there is a good deal of inflammable matter, however dormant it may be for a time, but when the torch is put to it, that which is within you may burst into flame.”

And that is what eventually happened to the young soldier. His friends, including Sally, felt it was time for him to marry. Realizing that things were getting too heated in their relationship, Sally decided to make a visit home to Ceelys, but not before she received another letter from George. It read, “I beg to know when you set out for Hampton and when you expect to return to Belvoir. I shall thereby hope for your return before I get down, for the disappointment of not seeing your family would give me much concern.”

At Ceelys, Sally returned to the life of carefree youth, with parties, dinners and no responsibility, if only for a little while. Then her life began to unravel: After only several days of illness, her father-in-law died and was buried on Belvoir land. (A monument stands at the gravesite today in his memory.) Shortly after his death and Sally’s return to Belvoir, George William left for a stay in England, worried that there was a conspiracy to rob him of his Yorkshire lands. Sally, devastated by the death of Sir William and lonely at Belvoir after her husband’s departure, wrote in the Fairfax family book, “Misfortune seldom comes alone. We do not ever appreciate something until we have lost it.”

These forlorn days gave Sally much time for introspection and improving her garden. But her eyes would turn toward Mt. Vernon. In her grief, her heart reached out to Washington, but her mind told her that relationship could never be. She was now a Fairfax, and a Fairfax she must remain. Sally decided what she must do: Encourage her young lover to find a wife. For in the near future, she realized, her life would most likely be in England with her husband. In America, there was also increasing talk of independence.

George Washington, meanwhile, struggled with his own emotions. He reached the conclusion that no matter how he felt about Sally, there was no future for them. The wife of his best friend, the future Lady Fairfax, what could he offer her? They would be ostracized by society if their relationship went any further. The last time he had visited Sally, she told him that he must transmute his feelings into his career. He would do that, but not before expressing his true feelings for her. He would allow, this one time, his emotions to have free rein, and then go on with his life.

On November 25, 1758, George Washington fought for the last time under the British colors when he planted the flag on the ruins of Fort Duquesne. He returned to Mt. Vernon and wrote his famous letter to Sally Fairfax, one she would forever treasure. He then married a sweet young widow, Martha Custis, whom he had met and spent some time with. By making her his wife, on January 6, 1759, Washington added to his fortune at least $100,000. The new Martha Washington, with her two small children, would provide him with a home life such as he had never known. He, in turn, was becoming nationally recognized, was an excellent business manager and would always respect her as his lady and wife.

His letter to Sally Fairfax apparently was in answer to her own to him congratulating him on his forthcoming marriage:

...Tis true I profess myself a votary to love. I acknowledge that a Lady is in the case: and, further, I confess that this Lady is known to you. Yes, Madam, as well as she is to one who is too sensible of her Charms to deny the Power whose influence he feels and must ever submit to. I feel the force of her amiable beauties in the recollection of a thousand tender passages that I could wish to obliterate till I am bid to revive them; but Experience alas alas! sadly reminds me how impossible this is, and evinces an Opinion, which I have long entertained, that there is a Destiny which has the sovereign control of our actions, not to be resisted by the strongest efforts of Human Nature.

You have drawn me, my dear Madam, or rather have I drawn myself, into an honest confession of a Simple fact. Misconstrue not my meaning, ‘tis obvious; doubt it not, nor expose it. The world has no business to know the object of my love, declared in this manner to you, when I want to conceal it. One thing, above all things, in this World I wish to know and only one person of your acquaintance can solve me that, or guess my meaning—but adieu to this till happier times, if ever I shall see them. …

Sally, ever conscious of the troubles any new letters could create, pretended not to understand his confession—his allusions to her. This indifference prompted another letter from Washington: “Do we still misunderstand the true meaning of each other’s letters? I think it must appear so, tho I would feign hope the contrary, as I cannot speak plainer without—but I’ll say no more and leave you to guess the rest.”

After Washington brought his bride back to Mt. Vernon, Sally and Martha became friends and spent many evenings at both George’s home and at Belvoir. The women were both secure in their life stations; Sally, with wealth and future title, was a respectable married woman who was also secretly sure of Washington’s passionate love. Martha, now Mrs. George Washington, was equally sure of Washington’s devotion, for she had not only provided him with a fortune but an already made family, and he adored her children. So the two women were content in their friendship.

George William, meanwhile, grew increasingly nervous about his English landholdings. He insisted that he and Sally go to England. He hoped to return to America at a later date. He placed the renting of Belvoir in the hands of his friend, Washington, and Sally and he sailed for England in 1773. First they went to London for a short time, then on to Yorkshire, where he renovated the house and purchased his “coach and six.” Still, he was the object of great antipathy, and soon George William wrote to Washington, saying they were obliged to leave Yorkshire, to sell his “coach and six” and to get out of the way of his relatives there, who gladly would have turned him over to the authorities and usurped his lands. He admitted that at any time he expected to be seized by the authorities and had only recently been saved from persecution by a relative with influence with the court.

While Washington’s star ascended, and he became famous and wealthy, Sally’s star plummeted. The Fairfaxes relocated to Bath, England, and a greatly reduced lifestyle. She was unhappy with her servants who “carry themselves very high and are insolent above all description.” British women snubbed her, and she had few friends. Sally, the proud daughter of Col. Cary—Sally, the Williamsburg belle and mistress of Belvoir, the love of George Washington—was saddened and humbled, and further devastated when her husband died in 1787. And then her own health began to decline. Lonely, she wrote to her sister-in-law in Virginia: “Weeping has robbed me of sight. There was a time of my life when I should not have been well pleased to hear of the union between a daughter of yours and Mr. – but, thank God, I have outlived those prejudices of education and know now that the worthy man is to be preferred to the high born who has not merit to recommend him.”

Sally’s dreams had crumbled. She never became Lady Fairfax. That honor would pass to her sister, Elizabeth, who married Sally’s brother-in-law Bryan, who received the family title.

Alone now in a foreign land, Sally’s auburn hair turned to silver. Her fingers became stiff with arthritis, and her feet suffered with gout. She still had the proud bearing of an aristocrat, however, and welcomed the visits of what few friends she had. She knew that Belvoir had burned, in 1783, and any hopes of returning there were gone. She wrote to her sister-in-law in Virginia that she longed to return, but her health “would not permit” her to cross the Atlantic again. She also knew that if she could return, she would have to live on the generosity of her family, for she had few funds of her own.

George Washington died in 1799. Martha Washington died in 1802. Sally Fairfax died at her home in England in 1811. No friends or family were with her at the time, and only her servants attended her. Her coffin was carried down to the quaint, small church at Writhington, in Somerset, and her body laid to rest next to that of her husband.

Perhaps one thought had sustained her into old age: that she, in her own way, a way she would never divulge to anyone, had taken a bright country youth under her wing while living at Belvoir. She had taught him manners, how to dress, how to write and spell correctly, how to dance formally, and especially how to choose and to read the classics. Even more, she’d taught him how to set goals for himself and aim high in life, which would enhance his career. And it was she who had taught him how to act around gentlewomen, how to court a lady. She had taught him the art of love, until she knew he was ready to make a good marriage and treat a wife properly.

And Washington? As with all things, he had faced his personal life with both honesty and courage. So the question remains: Had he not loved Sally so passionately, could he have loved Martha so well?

Attachments:

http://www.virginialiving.com/virginiana/history/the-lady-of-belvoir/

If there is a ghost at the Fort Belvoir military base in Northern Virginia, it is that of Sally Fairfax, wandering about her garden, admiring her favorite daffodils while eagerly listening for the sound of hoofbeats and the approach of her young caller: George Washington.

In the spring, the daffodils still bloom, but Belvoir is no more. Long ago, the charred ruins of the lovely mansion crumbled to the ground along with its memories of candlelit balls and the sounds of coaches on cobblestone. Yet a love story remains. It is little known and less spoken of, but still an integral part of America’s colonial history. It is a chapter in the life of the American hero, George Washington, who loved, passionately, the lady at Belvoir his neighbor and the wife of his best friend, George William Fairfax. Proper credit has never been given Sally for the important role she played in Washington’s early life. Instead, she has been regarded mainly as a flirtatious Southern belle, a brainless beauty. Untrue!

The eldest and most fascinating of the four daughters of Col. Wilson Cary, owner of Ceelys Plantation near Hampton, Sally was born in 1730 to great wealth and luxury. The Cary plantation was the center of society along the lower James River. Gentry from near and far often visited, as did officers from foreign ships that sailed into port.

As the colonel was a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, the family, during sessions, stayed at their Williamsburg townhouse and took advantage of the town’s many social events, including Assembly balls at the Governor’s Palace. A strict guardian of his four pretty daughters—Sally (Sarah), Mary, Anne and Elizabeth—the colonel was quick to discourage any suitor who was not wealthy, not from a prominent family or otherwise unacceptable as a future son-in-law. He was particularly selective of Sally’s beaux for, as everyone knew, she was his favorite. He had personally overseen her education. Let a man without wealth or family background approach the colonel for permission to call upon Sally, and he would be sent packing with the words, “If that is your mission here, sir, you may as well order your horse. My daughter is accustomed to her coach and six.”

Sally, at age 18, was highly educated and intelligent, knowledgeable of world affairs, music, art, literature and dance. She read books from her father’s vast library. She was also feminine, a coquette—and, as yet, unmarried. Many of her friends were not only married but had become parents as well. Not that Sally seemed to mind, for beaux were still plentiful and parties numerous, and she had every material wish fulfilled by her doting father. She spent her days visiting friends, attending teas (often with her mother or sisters) and learning the latest gossip of Williamsburg.

Her evenings were for merriment. It was no surprise when the family received an invitation to attend the Governor’s Ball during the session of 1747. What was serendipitous was that Sally would meet her future husband, George William Fairfax, that evening. As everyone knew, he was from Northern Virginia and lived at the magnificent Belvoir mansion on the Potomac, along with his father, Sir William Fairfax. And he was heir to the famous family title that would one day make him Lord Fairfax.

Sally was expert in dancing, and she dressed expensively, her auburn hair coiffed beautifully by her attendant. She at once caught the eye of the 23-year-old Fairfax. He also caught Sally’s attention, with his powdered wig, handsome evening costume and aristocratic features. Each queried friends about the other. When George William learned that not only were the Cary women beautiful but also from a family of great wealth, property and history (dating back to the 1400s in England, as did his own), he at once asked to call on Sally. He was accepted by the entire family, one of whom informed him, “I know of no family which has ever possessed nobler specimens of womanhood.”

George William was hooked. He at once wrote to his cousin, Robert, in England, the only man who stood between him and the Fairfax title: “Attending here on the General Assembly, I have had several opportunities of visiting Miss Cary, a daughter of Colonel Wilson Cary, and finding her amiable person to answer all the favourable reports made, I addressed myself and having obtained the young lady’s and her parents’ consent, we are to be married on the 17th instant. Colonel Cary wears the same coat of arms as the Lord Hunsdon.”

Col. Cary thoroughly researched the Englishman’s background and happily discovered that not only did he stand to inherit Belvoir, with its 2,700 acres in northern Virginia, but he also owned properties in Yorkshire; the famous Leeds Castle in England was among the Fairfax possessions. Yes, if asked, he would be pleased to hand over his daughter to such a prominent man, never mind that there was an arrogance about the future lord, a noblesse oblige that puzzled some and awed others. Love had little to do with it.

How did Sally react to all this? She was dazzled with the prospects. One day, she reasoned, she would become Lady Fairfax. None of her friends could make such a claim. Belvoir would be her home, to live in, to entertain in, to do with as she liked. She had heard much good about the Fairfax men and their great wealth and position in the colony. And so, on the 17th of December, 1747, she and George William were married and at once left for Belvoir, the mansion perched high on a bluff above the mighty Potomac.

As the coach rounded the curved drive in front of Belvoir, Sally caught her first glimpse of her new home and at once fell in love with it. Built by her father-in-law, Sir William Fairfax, who was still in residence, the mansion was without a hostess as the owner was a widower and lived there with his two sons, George William and young Bryan. His two daughters had married well: Anne to Lawrence Washington, the neighbor at Mt. Vernon, and Sarah to John Carlyle, the merchant prince at Alexandria, short miles from Belvoir.

Seeing Sally’s awe of the mansion, George William is known to have commented, “It’s a nice little cottage in this wooded land.” Indeed. A large hallway ran the width of the home, allowing river breezes to cool the interior. Off the hall were four high-ceilinged rooms, all magnificently furnished with carved mahogany and cherry furniture. Persian rugs covered the hardwood floors, and oil portraits and landscapes hung on the walls. Sally’s own chambers were equally extravagant: There was a great curtained bed with steps leading up to it, a dressing table with large mirror in gilt frame, a chest on chest of drawers, comfortable chairs, a tea table complete with silver tea service and candelabra, and a large fireplace.

While Sally was delighted with the estate, she completely lost her heart to Belvoir’s magnificent flower garden, 160 feet wide and 215 deep. Patterned after a garden in the county of Stirling, Scotland, the garden contained tulips, violets, roses, hollyhocks and her special flower, the daffodil, of various varieties.

Determined not to become overwhelmed by all this grandeur, Sally soon took her place as chatelaine of this new mansion. Neighbors told her that it outshone the other Potomac homes—Mt. Vernon of the Washington family and Gunston Hall, George Mason’s home. Her husband, eager to show off his prized new bride, suggested an evening when she would meet his family and friends from Alexandria and the neighboring area. And they soon came for an evening of festivity, not only including dinner but dancing as well, as was the custom of the times. No one knows exactly what Sally wore that evening to greet her guests, but perhaps it was the gown that would one day be returned with her personal things to the Cary family and now rests, carefully cared for, in the Valentine Richmond History Center in Richmond: an off-white silk brocade gown embroidered with multicolored flowers. Pearls were the fashion, and it is known that Sally had beautiful ones to wear.

And the guests? Among them were John and Sarah Carlyle, her new sister-in-law, with whom Sally would soon become good friends. The Lawrence Washingtons were there as well: Anne Washington, George William’s other sister and, loved to dance as much as Sally did.

With the Washingtons that night came a tall, broad-shouldered young stepbrother, George Washington, who now lived at Mt. Vernon. Lawrence had invited him. The young man stood before Sally, staring at her steadily, for never had he seen such an elegant woman. Manners would have kept Sally from staring back, but briefly she saw the tall 16-year-old, fresh from the farm where he had lived with his mother and other siblings. He was plainly dressed, his dark brown hair drawn back from his strong face in a queue, large hands and feet waiting for the rest of his frame to grow into them, George Washington continued to stare at Sally with a masculine assurance, head held high, looking directly into her eyes with his own of blue-gray.

The evening was lively, with good food, conversation and dance. When it ended, Sally invited George to visit as often as he chose. He chose to visit very often, and was awed by how knowledgeable was the wife of George William. They spoke of books and plays. Sally introduced him to Joseph Addison’s play Cato (1713) and gave him her own copy, which she had brought from Ceelys, to take home and study. George studied it carefully, and when they met again they acted out portions of the drama, with Sally being Marcia and he, Juba. Often and throughout his life, in person and in letter, George would refer to Sally as “Marcia.”

A great friendship sprang up between Sally and Washington. The Fairfax men, Sally soon realized, were eager for the young stepbrother of their neighbor to improve his mind and achieve a career for himself. Unlike his two brothers, George had not had a formal education; his father had died before he could send him to England for schooling. While Lawrence wished that George would follow his own career at sea, George’s mother put an end to that idea. And so now his education would be up to his brother and the Fairfaxes, including Sally.

Sally took her task to heart. She instilled in him a desire to make something of himself. She read to him about famous leaders throughout history, urged him to enter the military and to achieve, achieve, achieve. She helped him with his writing and spelling, and with his manners in social and political situations. In addition to all this, the Fairfax men introduced him to influential military and political leaders. When the Fairfax cousin, Lord Thomas Fairfax, owner of almost all of Northern Virginia and land farther to the west, came to stay at Belvoir for a year, he at once took a liking to young George and wrote to George’s mother, “Young George has what my friend, Mr. Addison, was pleased to call the intellectual conscience. The Lord deliver him from the nets of those spiders, called women, who will cast for his ruin. I wish I could say that he governs his temper for he is subject to attacks of anger on provocation, and sometimes without just cause. But, time will cure him.”

The letter summed up the elderly lord’s opinion of women, for he had never recovered from being jilted on the eve of his own wedding by an Englishwoman. His attitude toward them, however, did not sway young George, who, as everyone knew, had had many youthful crushes on girls. Despite the difference in attitudes, the two men became good friends, and when Lord Thomas asked George to survey his lands to the west, he accepted at once.

This surveying trip, made with Sally’s husband, George William, gave Washington a boost of confidence. He was now earning his own money and gaining a knowledge of terrain he had not visited before. He matured rapidly.

Meanwhile, Sally busied herself with hostess duties. When foreign vessels docked at Alexandria, the ships’ officers were invited to Belvoir for evenings of dinner, dancing and entertainment. Sally, in her finery, the latest fashions from Philadelphia and New York, was at her best. To offer a good table was a point of honor of every hostess, and Sally had been well schooled by her mother. Breads and cakes were baked daily, the woods around Belvoir were full of game and the river with fish, and from farther downstream came oysters and crabs. There were vegetables, grown in the Belvoir garden, as well as wines: Madeira, claret and port were served along with beer made from the native persimmon.

One evening as she danced with George Washington, Sally mentioned that she was surprised at his expertise with the dance. He replied that his mother was an expert dancer and had taught him herself. Sally saw that he knew all the country dances as well as the Virginia reel and needed only a little more teaching about the minuet, which she was happy to provide. If her husband, an undemonstrative man, noticed their closeness, he was tolerant and never voiced an objection.

Not so his younger brother, Bryan. He scolded Sally about her flirtation with George. This annoyed Sally, who told her husband of Bryan’s remarks, and the subsequent rift between the two brothers lasted for quite a time. Sally never really forgave Bryan for what she felt was his intrusion into her life.

By now, George had begun a military career and was being talked about. He was showing great promise as a leader. He would write Sally from various camps where he was on duty, and in one such letter he writes, “I should think our time more agreeably spent, believe me, in playing a part in Cato with myself doubly happy in being the Juba to a Marcia as you must make.” He then quotes from the play: “And in the shock of charging hosts remember what glorious deeds should grace the man who hopes for Marcia’s love.”

When George’s fascination for Sally turned to love, it is not known. But his letters grew warmer as he matured, and when Sally suspected that they were becoming amorous, she suggested that he continue to write but to direct them in care of a friend and she would get them.

When George visited home, he found that Sally was usually busy with her friends. In 1755, he writes her, apparently frustrated: “I have hitherto found it impracticable to engage one moment of your attention. If these are fearful apprehensions only, how easy to remove my suspicions, enliven my spirits and make me happier than the day is long by honoring me with a correspondence which you did partly promise to do.”

Sally, not wanting him to stop writing or visiting, continued to receive his letters and visits. Each time she inspired him to climb higher, telling him he was destined for greatness. And each time his passion for her grew—though he held these emotions under a rigid control, for now was not the time to express his feelings. Yet, years later, he would speak to Martha Washington’s granddaughter and say, “In the human being there is a good deal of inflammable matter, however dormant it may be for a time, but when the torch is put to it, that which is within you may burst into flame.”

And that is what eventually happened to the young soldier. His friends, including Sally, felt it was time for him to marry. Realizing that things were getting too heated in their relationship, Sally decided to make a visit home to Ceelys, but not before she received another letter from George. It read, “I beg to know when you set out for Hampton and when you expect to return to Belvoir. I shall thereby hope for your return before I get down, for the disappointment of not seeing your family would give me much concern.”

At Ceelys, Sally returned to the life of carefree youth, with parties, dinners and no responsibility, if only for a little while. Then her life began to unravel: After only several days of illness, her father-in-law died and was buried on Belvoir land. (A monument stands at the gravesite today in his memory.) Shortly after his death and Sally’s return to Belvoir, George William left for a stay in England, worried that there was a conspiracy to rob him of his Yorkshire lands. Sally, devastated by the death of Sir William and lonely at Belvoir after her husband’s departure, wrote in the Fairfax family book, “Misfortune seldom comes alone. We do not ever appreciate something until we have lost it.”

These forlorn days gave Sally much time for introspection and improving her garden. But her eyes would turn toward Mt. Vernon. In her grief, her heart reached out to Washington, but her mind told her that relationship could never be. She was now a Fairfax, and a Fairfax she must remain. Sally decided what she must do: Encourage her young lover to find a wife. For in the near future, she realized, her life would most likely be in England with her husband. In America, there was also increasing talk of independence.

George Washington, meanwhile, struggled with his own emotions. He reached the conclusion that no matter how he felt about Sally, there was no future for them. The wife of his best friend, the future Lady Fairfax, what could he offer her? They would be ostracized by society if their relationship went any further. The last time he had visited Sally, she told him that he must transmute his feelings into his career. He would do that, but not before expressing his true feelings for her. He would allow, this one time, his emotions to have free rein, and then go on with his life.

On November 25, 1758, George Washington fought for the last time under the British colors when he planted the flag on the ruins of Fort Duquesne. He returned to Mt. Vernon and wrote his famous letter to Sally Fairfax, one she would forever treasure. He then married a sweet young widow, Martha Custis, whom he had met and spent some time with. By making her his wife, on January 6, 1759, Washington added to his fortune at least $100,000. The new Martha Washington, with her two small children, would provide him with a home life such as he had never known. He, in turn, was becoming nationally recognized, was an excellent business manager and would always respect her as his lady and wife.

His letter to Sally Fairfax apparently was in answer to her own to him congratulating him on his forthcoming marriage:

...Tis true I profess myself a votary to love. I acknowledge that a Lady is in the case: and, further, I confess that this Lady is known to you. Yes, Madam, as well as she is to one who is too sensible of her Charms to deny the Power whose influence he feels and must ever submit to. I feel the force of her amiable beauties in the recollection of a thousand tender passages that I could wish to obliterate till I am bid to revive them; but Experience alas alas! sadly reminds me how impossible this is, and evinces an Opinion, which I have long entertained, that there is a Destiny which has the sovereign control of our actions, not to be resisted by the strongest efforts of Human Nature.

You have drawn me, my dear Madam, or rather have I drawn myself, into an honest confession of a Simple fact. Misconstrue not my meaning, ‘tis obvious; doubt it not, nor expose it. The world has no business to know the object of my love, declared in this manner to you, when I want to conceal it. One thing, above all things, in this World I wish to know and only one person of your acquaintance can solve me that, or guess my meaning—but adieu to this till happier times, if ever I shall see them. …

Sally, ever conscious of the troubles any new letters could create, pretended not to understand his confession—his allusions to her. This indifference prompted another letter from Washington: “Do we still misunderstand the true meaning of each other’s letters? I think it must appear so, tho I would feign hope the contrary, as I cannot speak plainer without—but I’ll say no more and leave you to guess the rest.”

After Washington brought his bride back to Mt. Vernon, Sally and Martha became friends and spent many evenings at both George’s home and at Belvoir. The women were both secure in their life stations; Sally, with wealth and future title, was a respectable married woman who was also secretly sure of Washington’s passionate love. Martha, now Mrs. George Washington, was equally sure of Washington’s devotion, for she had not only provided him with a fortune but an already made family, and he adored her children. So the two women were content in their friendship.

George William, meanwhile, grew increasingly nervous about his English landholdings. He insisted that he and Sally go to England. He hoped to return to America at a later date. He placed the renting of Belvoir in the hands of his friend, Washington, and Sally and he sailed for England in 1773. First they went to London for a short time, then on to Yorkshire, where he renovated the house and purchased his “coach and six.” Still, he was the object of great antipathy, and soon George William wrote to Washington, saying they were obliged to leave Yorkshire, to sell his “coach and six” and to get out of the way of his relatives there, who gladly would have turned him over to the authorities and usurped his lands. He admitted that at any time he expected to be seized by the authorities and had only recently been saved from persecution by a relative with influence with the court.

While Washington’s star ascended, and he became famous and wealthy, Sally’s star plummeted. The Fairfaxes relocated to Bath, England, and a greatly reduced lifestyle. She was unhappy with her servants who “carry themselves very high and are insolent above all description.” British women snubbed her, and she had few friends. Sally, the proud daughter of Col. Cary—Sally, the Williamsburg belle and mistress of Belvoir, the love of George Washington—was saddened and humbled, and further devastated when her husband died in 1787. And then her own health began to decline. Lonely, she wrote to her sister-in-law in Virginia: “Weeping has robbed me of sight. There was a time of my life when I should not have been well pleased to hear of the union between a daughter of yours and Mr. – but, thank God, I have outlived those prejudices of education and know now that the worthy man is to be preferred to the high born who has not merit to recommend him.”

Sally’s dreams had crumbled. She never became Lady Fairfax. That honor would pass to her sister, Elizabeth, who married Sally’s brother-in-law Bryan, who received the family title.

Alone now in a foreign land, Sally’s auburn hair turned to silver. Her fingers became stiff with arthritis, and her feet suffered with gout. She still had the proud bearing of an aristocrat, however, and welcomed the visits of what few friends she had. She knew that Belvoir had burned, in 1783, and any hopes of returning there were gone. She wrote to her sister-in-law in Virginia that she longed to return, but her health “would not permit” her to cross the Atlantic again. She also knew that if she could return, she would have to live on the generosity of her family, for she had few funds of her own.

George Washington died in 1799. Martha Washington died in 1802. Sally Fairfax died at her home in England in 1811. No friends or family were with her at the time, and only her servants attended her. Her coffin was carried down to the quaint, small church at Writhington, in Somerset, and her body laid to rest next to that of her husband.

Perhaps one thought had sustained her into old age: that she, in her own way, a way she would never divulge to anyone, had taken a bright country youth under her wing while living at Belvoir. She had taught him manners, how to dress, how to write and spell correctly, how to dance formally, and especially how to choose and to read the classics. Even more, she’d taught him how to set goals for himself and aim high in life, which would enhance his career. And it was she who had taught him how to act around gentlewomen, how to court a lady. She had taught him the art of love, until she knew he was ready to make a good marriage and treat a wife properly.

And Washington? As with all things, he had faced his personal life with both honesty and courage. So the question remains: Had he not loved Sally so passionately, could he have loved Martha so well?

Attachments:

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

CAVA1990

()

Date: July 22, 2014 07:29AM

Back in the 1950's my relatives had their house torn down because it was so badly haunted. They could no longer handle living there and couldn't sell it because it had gained a reputation. It's now a restaurant.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

EOD building @ Ft. Belvoir

()

Date: July 22, 2014 01:58PM

The EOD building at Ft. Belvoir is haunted, everyone that I know who was stationed there says the place is freaky and a few techs that I know saw a mist floating around - these techs I wouldn't hesitate in a second to go downrange with and were not bullshit artists.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

sad but true

()

Date: July 22, 2014 02:18PM

I work in a hospital, and in a place where death is common, I kind of learned how to just shrug things off and move on. This is different, and kind of both creeps me out, and brings tears to my eyes.

A cardiologist at our hospital died a couple of weeks ago. His house caught on fire. His wife, along with their 2 children also died during the accident. All four of them were found in the bedroom hugging each other.

There’s this kid, 7 years old, his doctor was a pediatrician at our hospital, been there a lot actually. The pediatrician was at a loss to with what to do with the kid. He was brought there by his mother, because the kid insisted he has been talking to his father a lot. His father died a couple years ago, and I’m not sure how or why. The pediatrician found nothing wrong with the kid.

A couple of days ago. the kid insisted on seeing his pediatric doctor, he didn’t say why, but was persistent. He kept bugging his mom to bring him to the doctor immediately. End of the day, she brings his kid to the hospital. Upon entering, the kid just stopped. In the lobby there was a photo of the deceased cardiologist, with flowers and well wishes. The kid sees it and tugs at his mom, “That’s the guy who talked to me a couple of days ago, he told me to tell [pediatric doctor] not to cry anymore, he said they’re all ok and happy.” So the mom takes the kid to his doctor, and the pediatric doctor is just, shocked and overwhelmed at the same time. The pediatric doctor was close friends with the cardiologist, and have been in a sad state these past couple of days.

The part that freaks me out is that the cardiologist never met the kid patient ever. I do believe that science can explain most things, but maybe not everything. If there was an “I see dead people kid” in real life, I’d bet that’s the kid.

A cardiologist at our hospital died a couple of weeks ago. His house caught on fire. His wife, along with their 2 children also died during the accident. All four of them were found in the bedroom hugging each other.

There’s this kid, 7 years old, his doctor was a pediatrician at our hospital, been there a lot actually. The pediatrician was at a loss to with what to do with the kid. He was brought there by his mother, because the kid insisted he has been talking to his father a lot. His father died a couple years ago, and I’m not sure how or why. The pediatrician found nothing wrong with the kid.

A couple of days ago. the kid insisted on seeing his pediatric doctor, he didn’t say why, but was persistent. He kept bugging his mom to bring him to the doctor immediately. End of the day, she brings his kid to the hospital. Upon entering, the kid just stopped. In the lobby there was a photo of the deceased cardiologist, with flowers and well wishes. The kid sees it and tugs at his mom, “That’s the guy who talked to me a couple of days ago, he told me to tell [pediatric doctor] not to cry anymore, he said they’re all ok and happy.” So the mom takes the kid to his doctor, and the pediatric doctor is just, shocked and overwhelmed at the same time. The pediatric doctor was close friends with the cardiologist, and have been in a sad state these past couple of days.

The part that freaks me out is that the cardiologist never met the kid patient ever. I do believe that science can explain most things, but maybe not everything. If there was an “I see dead people kid” in real life, I’d bet that’s the kid.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

Marriott Manassas Battlefield

()

Date: July 26, 2014 12:07AM

I stayed at an Inn by Marriott Manassas Battlefield Park. I checked in the room, put my suit case down, and met friends for dinner. When I returned the bottom drawer where the TV sat was pulled out. Nothing was missing in the room. I called the front desk and requested a room change. The room was changed to the third floor. On the nightstand near the bed I placed phone to charge, my glasses, a bottle of water, and my purse. I went to sleep and woke up to go to bathroom. Purse on nightstand went missing. I looked around the room and then saw a lump in the bed. My purse was in the bed with the covers over it. It was really strange. When I went to sleep, the purse was on the night stand. Understand that Manassas Battlefield Park is 1.2 miles away.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

my ghost experience

()

Date: July 26, 2014 07:52AM

Wow great site! Loved reading all the stories and have one of my own....Over thirty years ago before my first husband and I were married I lived with my soon to be ex-sister-in-law for about a month in Fredericksburg VA. Her and her husband built their house over at Twin Lakes which during the war between the states was a battle medical area and weapons storage. At least, that was what I was told. One night when the family went to the beach only me and two nephews were staying at the house. I was sleeping in my sister-in-law's daughter's room. In the middle of the night I was awaken for no apparent reason. I rolled over to my side to face a large picture window with closed curtains. It must have been a full moon because I can see the brightness of the moon through the curtains. Then suddenly I saw a shadow of what looked like a man crouching down with a rifle walking across the window outside wearing a flat type of cap that later I recognized as a confederate or union cap. I was frozen in my bed and very scared, but I rolled back over. I put the covers over my head and went back to sleep knowing that if he tried to get in the security alarm would be activated. Ironically, after that time I told my husband's family, and they told me about seeing shadows, hearing footsteps coming up the stairs from the basement and coming down the hall. Many years later when my son from that marriage grew to manhood he told me that he would hear footsteps and weird things happen at aunt Pat's house.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

i did too

()

Date: July 27, 2014 08:06PM

Massanutten Military Academy Wrote:

-------------------------------------------------------

> Some years ago when I was a cadet at the

> Massanutten military Academy and I saw some ghost

> sightings on the fourth floor of benchoff hall and

> Harrison hall. Also I heard voices and saw stuff

> in the basement of Sperry hall (under the former

> quartermaster) I believe they are more like evil

> spirits than ghosts because when they are sighted

> it feels ice cold and you feel like your soul is

> being dragged out of your body.

I was at Massanutten Military Academy as a cadet for summer school on the fourth floor of Benchoff, when at 3 am in the morning a ghost child crawled in my window (on the fourth floor) and crawled out my door. I was absolutely horrified.

-------------------------------------------------------

> Some years ago when I was a cadet at the

> Massanutten military Academy and I saw some ghost

> sightings on the fourth floor of benchoff hall and

> Harrison hall. Also I heard voices and saw stuff

> in the basement of Sperry hall (under the former

> quartermaster) I believe they are more like evil

> spirits than ghosts because when they are sighted

> it feels ice cold and you feel like your soul is

> being dragged out of your body.

I was at Massanutten Military Academy as a cadet for summer school on the fourth floor of Benchoff, when at 3 am in the morning a ghost child crawled in my window (on the fourth floor) and crawled out my door. I was absolutely horrified.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

amanda

()

Date: August 02, 2014 02:42PM

When I was a young girl I lived in this little house on TC Walker in Gloucester Va. It was me, my mom, and now step dad. Well every night around midnight I would wake up screaming and running to my mom's room complaining about a man being in my room. Cops were called, and they said there was no sign of any break in or man. Every night for months this happened. I would wake up to my toys being played with and the old man wanting to play. My mom was getting frustrated and wanted to see for herself. She stayed the night in my room with me, and yet again around midnight she woke up to me talking to somebody telling them I did not want to play and that I wanted to go to sleep. She then saw my toys going off.

Well after that we moved. We then got a phone call from the people that moved in after us asking if any of the family saw an old man. My mom explained the situation and sure enough the people were experiencing it too. Well, mom called the realtor and sure enough an old man died in my room around midnight. He was really sick and could never have children although he absolutely adored children. His room was turned into a hospital room (almost. ) My mom eventually found a newspaper clipping of the man and studied it with my dad and hid it. Well they asked me what he had looked like, and I was able to describe him to a t at the age of 8.

Well after that we moved. We then got a phone call from the people that moved in after us asking if any of the family saw an old man. My mom explained the situation and sure enough the people were experiencing it too. Well, mom called the realtor and sure enough an old man died in my room around midnight. He was really sick and could never have children although he absolutely adored children. His room was turned into a hospital room (almost. ) My mom eventually found a newspaper clipping of the man and studied it with my dad and hid it. Well they asked me what he had looked like, and I was able to describe him to a t at the age of 8.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

ghosts in house

()

Date: August 03, 2014 06:17PM

My sister and brother-in-law lived just down the road from the Manassas battle field and hospital. I just thought it was so wonderful and so much history when I grew up in PA. I vacationed in a place called Shenandoah Acres in Stuarts Draft, VA. My wife and I were helping them to move after twenty years. We were there for a few days. It is a two-story home with a large basement which was all redone with a wine room and a pool table and big sofa, where I had slept one night. That night I was awakened by a severe cramp in the end of my toe next to my big toe on my right foot that was on the arm of the sofa uncovered. I then fell asleep to be a woken up again. I wiggled it around, and I fell asleep to the same pain again covering it up thinking it was just cold. I fell asleep. Then awoke to my water bottle made a pop sound which I heard before at other times, but I heard it again a few minutes later. I was so tired that I dosed off and was awoken again by the same type of noise. I then took a drink and also blew air into it. Then I went to the restroom straight ahead on the left about ten feet away.

I also left the fan on and the door cracked a little, a humming noise helped me to sleep sometimes. I swear I could hear other loud noises coming from the room to my left with the door closed and to my right where the only light on coming from the television and the night light coming through the two windows from behind me. Time had gone by dosing to the clack of a pool table ball, I thought. I had gotten up to shut off the fan to the restroom, just sat on the couch covering up with the blanket, and heard a clack again then noises like someone was up stairs walking around. I then got up and turned the lights on yelling and realizing that there was a entity or two or maybe three with me. Everything was in boxes thirty or so to the right behind a closed door and many boxes to the left and behind me under the pool table. I looked around and did not see anything but got the hell out of there.

Now sitting on the couch up in the family room very quiet thinking about what just happened, I saw a limb on a tree move up and down erratic. I had gotten up to look. I saw no wind, no bird, or squirrel. About that time my father-in-law had gotten up. Now it's five o'clock; he had come downstairs to read his bible in the other room. Then I guess I fell asleep till eight o'clock. The same morning I had confronted my sister and brother-in-law about what happened to me, and they looked at each other and said they thought the house was still settling. They had strange things break on them at night especially in the basement. They never saw anything at all, but they were glad to move out of there.

I also left the fan on and the door cracked a little, a humming noise helped me to sleep sometimes. I swear I could hear other loud noises coming from the room to my left with the door closed and to my right where the only light on coming from the television and the night light coming through the two windows from behind me. Time had gone by dosing to the clack of a pool table ball, I thought. I had gotten up to shut off the fan to the restroom, just sat on the couch covering up with the blanket, and heard a clack again then noises like someone was up stairs walking around. I then got up and turned the lights on yelling and realizing that there was a entity or two or maybe three with me. Everything was in boxes thirty or so to the right behind a closed door and many boxes to the left and behind me under the pool table. I looked around and did not see anything but got the hell out of there.

Now sitting on the couch up in the family room very quiet thinking about what just happened, I saw a limb on a tree move up and down erratic. I had gotten up to look. I saw no wind, no bird, or squirrel. About that time my father-in-law had gotten up. Now it's five o'clock; he had come downstairs to read his bible in the other room. Then I guess I fell asleep till eight o'clock. The same morning I had confronted my sister and brother-in-law about what happened to me, and they looked at each other and said they thought the house was still settling. They had strange things break on them at night especially in the basement. They never saw anything at all, but they were glad to move out of there.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

battlefield ghost video

()

Date: August 09, 2014 02:43PM

I found this video on youtube and it has a ghost on the tape while they were filming out at Manassas battlefield.......

My family and I were on vacation in DC and we went to the Manassas battlefield. We video taped there, and later that day we were watching the tape and we noticed the woman dressed in white walking along the fenceline. There were no reenactments going on that day, and we didn't see her there. If you look to the left of the house, you will see a small black fence with a marker that encloses the graves of Mrs. Henry, her daughter, and her son. The ghost is walking away from the graves to just an open field. We are convinced that this was a paranormal experience.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G27tgEiUE2o

My family and I were on vacation in DC and we went to the Manassas battlefield. We video taped there, and later that day we were watching the tape and we noticed the woman dressed in white walking along the fenceline. There were no reenactments going on that day, and we didn't see her there. If you look to the left of the house, you will see a small black fence with a marker that encloses the graves of Mrs. Henry, her daughter, and her son. The ghost is walking away from the graves to just an open field. We are convinced that this was a paranormal experience.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G27tgEiUE2o

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

haunted malls

()

Date: August 11, 2014 12:35PM

I have heard that the Manassas Mall is haunted. A few people who have worked at one of the stores there (won't mention company since I'm currently employed with them) they only hear boxes and stuff being slammed on the ground in the stock room.

Also the World Market in Dulles, VA is severely haunted. I used to work there years ago. I did a few overnights there and have seen shadows walking through the aisles. There was the sound of shopping carts being slammed into the walls. Footsteps were heard every now and then, especially on the roof.

Also the World Market in Dulles, VA is severely haunted. I used to work there years ago. I did a few overnights there and have seen shadows walking through the aisles. There was the sound of shopping carts being slammed into the walls. Footsteps were heard every now and then, especially on the roof.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

Teresa Drive

()

Date: August 17, 2014 05:25AM

Something odd goes on in this house in chesapeake va. I lived there in 2004 for a few months only. It was odd and creepy from day one. Mirrors had delays in this house the kitchen and living room were always colder then the rest of house no matter what the A/C and/or temp outside was.

I often walked into kitchen to find fridge door and cabinets wide open. More than a few times my two large labs would not come into the kitchen and would hide down hallway if called for dinner or to go outside they would stand at end of hallway and growl into living area of house.

I often walked into kitchen to find fridge door and cabinets wide open. More than a few times my two large labs would not come into the kitchen and would hide down hallway if called for dinner or to go outside they would stand at end of hallway and growl into living area of house.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

Northern VA Parent

()

Date: August 24, 2014 05:33AM

The Family Dollar in Manassas off the main drag from 66, is haunted. I was there yesterday, when my two year old son and I were walking around. At one of the endcaps there was a display that had several medium sized balls that my son wanted, but we wouldn't allow him to have (He has several already). As we were walking away, I saw one of the balls (blue ball that my son liked) slip thru the side on its own, drop to the floor, and roll about 15 feet towards the front of the store towards my son. As I was putting the ball back, another ball, this time a red one, did the same thing. We got out of there real quick. FREAKY!

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

Leesburg resident

()

Date: September 05, 2014 11:57PM

I have had several encounters with spirits, but I am sensitive to them. I tend to see, hear, and sense them all the time. I was living on Smartts Lane for a few years in one of the townhomes and had a spirit in the house there. I was calling my dog one of the times, and she looked scared. She looked up at the spirit then looked over at me like she couldn't get by it because the spirit was standing in her way. She kept doing it as I kept calling her, so she finally slowly creeped around the figure in the hall and darted towards me after she passed it. I couldn't see the spirit, but I knew it was there. I have a K2 meter as well and had used that in my old houses and had several responses on it.

I had things happen in the neighborhood of Tavistock as well, which is weird because it used to be a farm there before the neighborhood was ever built. That was when I was living with my mother. I was lying in bed one night with 3 dogs on my bed, wasn't asleep yet. Then I heard this woman singing outside my door. She was singing for about a minute then I heard her scream, and it stopped, but it still echoed in my head. I looked down at the dogs, and all their ears were up, so I knew it wasn't just me. I have had the TV turn on by itself often. I had received phone calls on the home phone FROM the home phone which was very weird. That happened for a whole week and stopped the day someone I knew passed away. I have had one of our past dogs come to my room. I heard the sniffing at the door and the jingle from the collar, and I just ignored it. Then I heard as if a dog was chewing on a water bottle. I looked under the bed, and I saw the bottle. I still heard it, but nothing was biting it. I turned on my lights, and it was still going on; it never stopped, so I put on music to drown out the sound of the spirit of the dog.

I was in the basement another time and ended up falling asleep. When I woke up and looked up I saw a tall skinny man in a blue uniform with a hat that was flat on the top with gold buckles down his shirt. He was standing there in front of me just staring at me. After my second blink of an eye he was gone. Toys went off by themselves as well, but of course this could be debunked as faulty toys by all means.

In downtown, that store next to the restaurant that moved, the new age one, I've felt the presence of spirits inside that place before several times. Also in the antique shop across the street, downstairs has spirits as well there. Balls Bluff I have felt the presence of spirits and when videotaping there I have caught black figures go across my camera and my k2 meter went off there as well.

I had things happen in the neighborhood of Tavistock as well, which is weird because it used to be a farm there before the neighborhood was ever built. That was when I was living with my mother. I was lying in bed one night with 3 dogs on my bed, wasn't asleep yet. Then I heard this woman singing outside my door. She was singing for about a minute then I heard her scream, and it stopped, but it still echoed in my head. I looked down at the dogs, and all their ears were up, so I knew it wasn't just me. I have had the TV turn on by itself often. I had received phone calls on the home phone FROM the home phone which was very weird. That happened for a whole week and stopped the day someone I knew passed away. I have had one of our past dogs come to my room. I heard the sniffing at the door and the jingle from the collar, and I just ignored it. Then I heard as if a dog was chewing on a water bottle. I looked under the bed, and I saw the bottle. I still heard it, but nothing was biting it. I turned on my lights, and it was still going on; it never stopped, so I put on music to drown out the sound of the spirit of the dog.

I was in the basement another time and ended up falling asleep. When I woke up and looked up I saw a tall skinny man in a blue uniform with a hat that was flat on the top with gold buckles down his shirt. He was standing there in front of me just staring at me. After my second blink of an eye he was gone. Toys went off by themselves as well, but of course this could be debunked as faulty toys by all means.

In downtown, that store next to the restaurant that moved, the new age one, I've felt the presence of spirits inside that place before several times. Also in the antique shop across the street, downstairs has spirits as well there. Balls Bluff I have felt the presence of spirits and when videotaping there I have caught black figures go across my camera and my k2 meter went off there as well.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

weeeeeOOOOoooo

()

Date: September 06, 2014 12:45AM

Getting phone calls from your own number is not paranormal - it's a dirty trick that telemarketers use to get you to pick up the phone. I don't know why, because there is never anybody at the other end. But that's who it is...Google it.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

GHOST SIGHTING ON RT 29 TONIGHT!

()

Date: September 07, 2014 07:36AM

GHOST SIGHTING ON RT 29 TONIGHT! Wrote:

-------------------------------------------------------

> My wife just saw a ghost dressed as a Civil War

> soldier walking along Route 29, tonight at around

> 8pm. She said he was semi-transparent with naval

> blue pants walking away from the the battlefield

> in the direction of the intersection of Rt. 29 and

> Heathcote.

This happened again just before midnight on Wednesday 8/27 when she was coming home. This always seems to happen when she's by herself, and it really worries me as to what could happen if she or anyone else ever decided to stop.

-------------------------------------------------------

> My wife just saw a ghost dressed as a Civil War

> soldier walking along Route 29, tonight at around

> 8pm. She said he was semi-transparent with naval

> blue pants walking away from the the battlefield

> in the direction of the intersection of Rt. 29 and

> Heathcote.

This happened again just before midnight on Wednesday 8/27 when she was coming home. This always seems to happen when she's by herself, and it really worries me as to what could happen if she or anyone else ever decided to stop.

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

Joseph sambol

()

Date: September 11, 2014 08:41AM

We are here helping my sister in law move after twenty years.I was sleeping in the basement on large couch when I a woken by a sharp pain in the end of my toe next to my big toe. I fell asleep it happens again.I fell asleep awoken again wiggling it around pain went away and I also covered my feet with the blanket this time thinking it was just cold. Then my water bottle started crinkling,once I thought it nothing because I had heard it before but two times after that with in a period of a few minutes. I had used the restroom and l and left on the noise fan in there. I then sat on the couch hearing these god awful pounding and loud nnoises so I got up turned off the bathroom fan. I laid down,I was so tired and sleepy.then awoken by I thought was pool table ball in the pocket make a clack sat up to noise in the closed room to the left if me and noise to right like rusting around I thought someone was upstairs. Then I heard another ball clack at the pool table. I got my blanket and pillows and went up stairs just to find the door closed. I then sat on the couch and started seeing one limb only moving up and down.I had looked to see if it was squirrel or a bird or something and no wind either. Creepy (I remembered the Manassas battle fields and house just down the road.)

Re: Ghosts/hauntings in around Fairfax County

Posted by:

vienna resident

()

Date: September 11, 2014 09:24AM